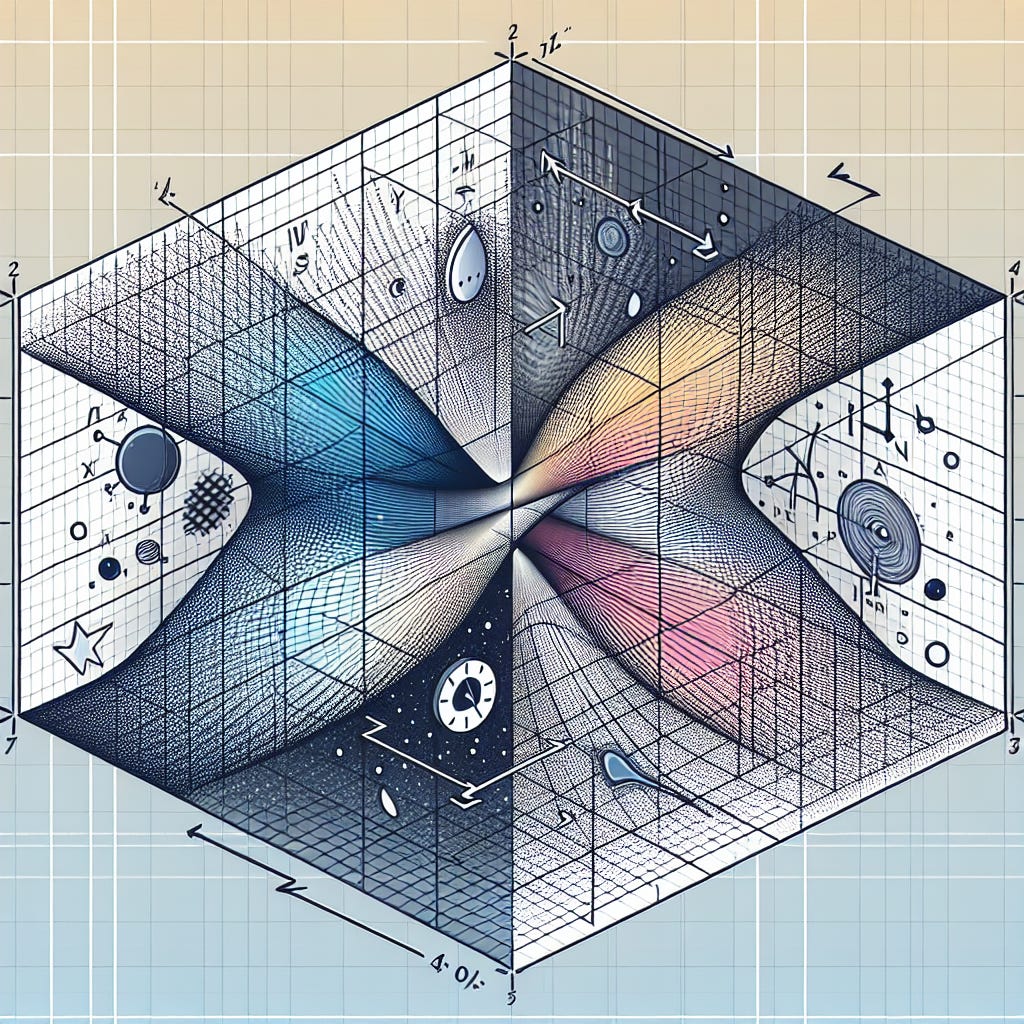

In 1908, three years after Albert Einstein proposed the Theory of Relativity, Hermann Minkowski offered a theory of his own. Minkowski, one of Einstein’s teachers, said the best way to explain the undeniable math of Relativity was to understand space and time as a single, four-dimensional entity—a continuum of space and time. More than a century later Minkowski Spacetime endures.

From Minkowski we therefore learned everything, literally everything, exists on a continuum. It should be unsurprising, then, that health and disease are no different.

When, for instance, does everyday sadness tip into the disease called Major Depression? Tricky. Psychiatrists use criteria that are, in essence, a way of gauging severity—in other words, determining where someone is on the continuum.

I was an incorrigible asshole during my mania episode a decade ago. As neuropsychologist Stephen Hinshaw wrote of his father’s mania, “When full-blown mania hits, irritability and anger are part of the picture just as much as euphoria and expansiveness.” I lashed out at my wife, lied to friends and family, and thought only of myself. But assholery wasn’t new to me—I was capable of it long before that. Still am.

And yet, just as the boiling frog is deceived by a gradual change in temperature, manics and their families typically miss the transition. Why? Because mania exists on a continuum with normal fluctuations in mood and personality. A friend once recounted how, toward the end of her own manic episode, she fell madly in love and eloped with a wonderful man. Her family, who had been frustrated with her odd behaviors, finally realized something was terribly wrong—because she is, and has always been, a lesbian.

The absence of a clear tipping point for disease is common, and not just in mental health. Most men over 50 will die with prostate cancer. Not of it, but with it. In other words it can be found on autopsy despite never affecting its host. Which is why screening for prostate cancer is controversial, and (like most other cancer screening) has failed to save lives in large trials. Finding cancer may be important, but only if it’s dangerous. Even cancer exists on a continuum.

Dementia is trickier still. At age 55 my memory isn’t getting better. I constantly forget why I entered a room and I’m terrible with names. But that’s not new. It’s just worse. (I think). Because cognitive impairment, like everything else, exists on a continuum.

Contrary to the claims of many, dementia can’t be diagnosed by MRI, or a blood test, or a PET scan. The new blood tests in the news do not test for Alzheimer’s (despite media and even expert claims). Instead, they test for the brain plaques that can be found in most who die with Alzheimer’s. But like prostate cancer those plaques are also present in most older people who don’t have any signs of Alzheimer’s.

Healthcare profiteers have learned how to monetize this grey-scale of health and disease, mostly by pretending the normal end of the continuum represents disease. The new dementia blood tests, like the pricey (but dangerous and ineffectual) new drugs for dementia, target the amyloid plaques that are so often found in perfectly normal brains.

The strategy of disease-ifying the normal works similarly with, for instance, cholesterol. Targeting cholesterol—instead of heart disease—has generated trillions in profits. Similarly, most partial blockages in the coronary arteries are a normal part of aging that the human body works with, or around. Targeting them with stents, a harmful practice in most instances, yields billions annually. And targeting prostate cancer, instead of deaths due to prostate cancer, has yielded an economy of biopsies, imaging, and treatment, overwhelmingly for cancers that pose no danger.

And so it goes with dementia, which is common (about 15% get it eventually). But concern about it is ubiquitous. Other than in extreme cases, properly diagnosing dementia is a slow, complicated, stuttering process. There is no single test and the continuum is different for different people. Making the diagnosis means ruling out mimics like strokes and other illnesses, carefully testing for hallmarks like short-term memory loss, and watching for progression over time. But it only works when doctors respect the continuum, and the individual on it.

So to my mom, asking about blood tests: They don’t work. And to a friend worried about her dad: For now he hasn’t hit the extremes, so keep hope alive.

But above all, keep in mind: Normal is not a disease. It is a shade of grey.

Share this post